Recreational research into Feudal Japan

Posts tagged Azuchi-Momoyama period

Resource: the Rijksmuseum

Jun 30th (a Shakkō (赤口))

I recently discovered that the Rijksmuseum, the Dutch national museum, has their collection searchable online with freely-usable images. They’ve got some cool stuff. Here are some highlights, focused on Japanese heraldry.

<img src="http://fireflies.xavid.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Screen-Shot-2016-06-30-at-13.48 traitement viagra naturel.50-300×114.png” alt=”Screen Shot 2016-06-30 at 13.48.50″ width=”300″ height=”114″ class=”alignnone size-medium wp-image-594″ srcset=”http://fireflies.xavid.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Screen-Shot-2016-06-30-at-13.48.50-300×114.png 300w, http://fireflies.xavid.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Screen-Shot-2016-06-30-at-13.48.50-768×293.png 768w, http://fireflies.xavid.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Screen-Shot-2016-06-30-at-13.48.50-1024×390.png 1024w, http://fireflies.xavid.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Screen-Shot-2016-06-30-at-13.48.50.png 1506w” sizes=”(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px” />

These details from “Arrival of a Portuguese ship”, c. 1600, show mon used on noren (fabric dividers). Of particular interest is the double bird mon that is reduced to a single bird on the smaller noren, showing a notable type of variation, and also the differences of background color between the large and small noren.

This box, from 1600-1650, shows wood sorrel and chrysanthemum mon with a “seven treasures” background pattern. The use of mother-of-pearl creates an interesting three-color effect, with two colors for the mon and one for the background.

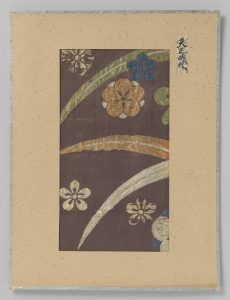

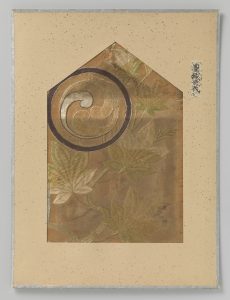

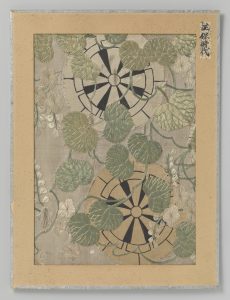

These fabric fragments, from 1573–1591, 1575–1600, and 1644–1648, respectively, show how mon designs could be used in embroidery.

And finally, this heraldic helmet with enormous gold ears is from 1575–1600.

I’m definitely a fan of museums making their collections widely available like this, having used the online collection from the Met extensively for context in my O-umajirushi translation. Enjoy the collection!

Primary Source: Kenmon Shokamon

Jun 5th (a Shakkō (赤口))

O-umajirushi is great for an idea of what mon were like in the Momoyama period, but what were they like before that? There are few earlier sources for mon other than depictions of battle scenes and similar. One that I have found, however, is Kenmon Shokamon (見聞諸家紋), which translates to “Various Observed Family Crests”. It’ss an excellent collection of a wide variety of earlier mon, some of which have been featured on this blog as “provincial samurai” mon. It was originally published around 1467–1470, and it features crests that were observed on the banners and camp curtains of the Ōnin War, which started the Sengoku period.(ja.wp:見聞諸家紋) It contains a variety of combinations and motifs that are rare or absent by the time of the later codifications. I recently got access to the full text of this source via Google Books and shenanigans, and it has plenty of interesting designs, featuring a wide selection of plovers and also including a phoenix, a horse, and a shrimp. It also features some unexpectedly pictorial designs that in some ways are more similar to the later Edo period designs than those in common use around the Momoyama period. Its selection of mon that combine multiple elements in different ways will be useful for those seeking to register mon in the SCA.

I haven’t had time for detailed analysis as of yet, but I present the text for your enjoyment:

Link: A Roll of Japanese Armory

Jun 12th (a Sembu (先負))

Just found an article that’s apparently been up for a while on the Academy of Saint Gabriel where the illustrious Solveig Throndardottir discusses family crests: A Roll of Japanese Armory. It’s short, but it features several pages of mon from the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, which is handy for those seeking a wider selection of Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573 to 1603) mon.

Names and Variation

Apr 5th (a Butsumetsu (仏滅))

Unlike English heraldry, which had an ornate system for describing heraldic devices that became divorced from the normal language, Japanese mon are named using simple phrases using reasonably standard Japanese for the time.1 The mon is named as its primary element, possibly prefixed with modifiers indicating its count, enclosure, style, or other characteristics. In some cases, the enclosure or style may itself has modifiers. Here is an example of a mon used by Inaba Masanari in the late 16th century: 隅切り角に三の字 or “sumi-kiri kaku ni san no ji”, which translates to “in a corner-cut square, the character ‘three’ ”.(SH:54)

These descriptive names lead to two ways mon can differ: they can have different names, or they can have the same name but be drawn differently acheter viagra allemagne. Different members of a family might use minor variations on the family mon, and different families that happened to use the same mon (say, in different provinces) ended up having slight differences due to artistic chance. These minor differences might not be expressed in the simple language of mon names, and would not be great for recognition in the heat of battle, but were in some cases taken seriously as a means of distinction. When a variant became well-known enough, it got its own name of the form “Family Charge”; e.g., the “Aoyama Coins”2, to distinguish it from other identically-named mon. Here are several different bellflower mon: the plain bellflower, two slightly-different but identically-named bellflowers in a circle enclosure, and a ‘shadowed’ or outline bellflower.

This gives you a taste of what common samurai mon might look like. We’ll go into more of the history and possible elements for mon next time.