Recreational research into Feudal Japan

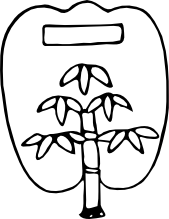

Mon of the Week: Fan with Bamboo

May 23rd (a Senshō (先勝))

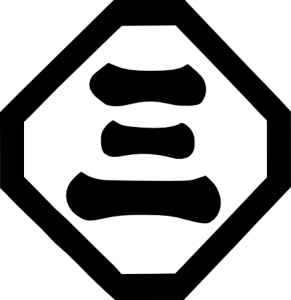

This week we look at another 15th-century rural samurai mon.(KJ:7) It shows what appears to be a nonfolding paper fan decorated with a bar, possibly the character for “one”, with a bamboo stem with leaves serving as the handle.

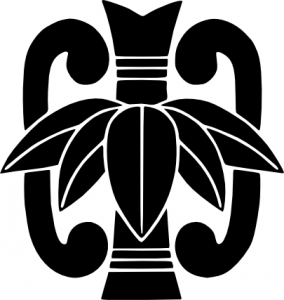

This is similar to a mon in use today, depicting a T’ang dynasty fan (唐団扇/tō uchiwa) with bamboo grass (笹/sasa).(IEJFC:39)

The shape of the fan is somewhat different in the more recent mon; my interpretation is that the design became more stylized as mon became standardized in the Edo period. This also shows how earlier mon had more flexibility in combining multiple unrelated elements in ways later mon would not. In addition, the bamboo stem in the modern one has become more stylized, somewhere between an actual bamboo stem and a fan rod. However, these two mon also show the consistency of mon in different eras, even as the ways mon were created, assigned, and used changed.

ADDED INFO:

A similar fan mon with a simplified, filled design and a simple post instead of the bamboo detail was used by Okudaira Nobumasa in the siege of Nagashino Castle in 1575.(SH:D5,59)

Mon of the Samurai

May 3rd (a Butsumetsu (仏滅))

Widespread battlefield use of mon seems to date to the Gempei War (1180-1185), where they were used on banners alongside Buddhist prayers, Shintō invocations, and heroic poetry. While it’s unclear if the two warring clans actually used the mon they were later associated with (butterfly for the Taira, gentian for the Minamoto), Heike Monogatari does contain clear references to mon on banners.(SH:10)

By the Muromachi period (1336–1573), samurai commonly adopted mon to identify themselves. A compilation of mon used by provincial samurai from around 1460–1470 shows some interesting things. While most of the elements are recognizable from modern mon, there are some elements and variation that did not persist. Without a central authority, samurai were less constrained in terms of shape, arrangement, and combination of elements than post-standardization mon from the Edo period.(KJ:7)

Here is a sample from this compilation: a classic paulownia mon with the insertion of the character 安 or ‘peace’. These are both common elements, though the location of a character in the middle of the flower is an unusual arrangement that did not end up becoming standard.(KJ:7)

On the Origin of Mon

Apr 26th (a Sembu (先負))

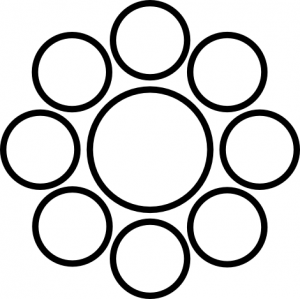

So, where did mon come from? While they’re often thought of as being used for battlefield identification, they didn’t start out that way. The first evidence of what became mon dates back to the Heian period (794–1185), when distinctive designs, some of which derive from Nara period (710–794) fabric patterns, were used by the Japanese imperial family and associated court nobility to indicate things like clan membership and religious affiliation.(ja.wp:家紋) One common design from this period is the simple “Shadowed, Nine Stars” design, shown below, used on an imperial ox-cart.(SH:4) “Shadowing” is the Japanese heraldic term for outlining. Note also the standard arrangement of large numbers of circular things, with one larger one in the middle, and the use of relatively large numbers in period mon.

Mon were initially associated with the court nobility and the Imperial family, and were used as decorations on clothing, carriages, and furniture rather than on banners and other stand-alone identification.(ja.wp:家紋) Still, they were a means of identification, and various court nobility families selected distinctive mon. In addition to geometric designs like this one, flowers, birds, and leaf patterns were common.(TM:45) Meanwhile, while warriors used distinctive banners for battlefield identification, these were of a simpler design. The first evidence of mon used for battlefield identification is in the Gempei War at the close of the Heian Period.(SH:10) We’ll look at some of these mon next time.Watch movie online Get Out (2017)

Names and Variation

Apr 5th (a Butsumetsu (仏滅))

Unlike English heraldry, which had an ornate system for describing heraldic devices that became divorced from the normal language, Japanese mon are named using simple phrases using reasonably standard Japanese for the time.1 The mon is named as its primary element, possibly prefixed with modifiers indicating its count, enclosure, style, or other characteristics. In some cases, the enclosure or style may itself has modifiers. Here is an example of a mon used by Inaba Masanari in the late 16th century: 隅切り角に三の字 or “sumi-kiri kaku ni san no ji”, which translates to “in a corner-cut square, the character ‘three’ ”.(SH:54)

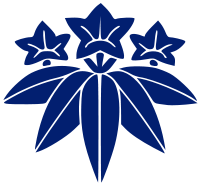

These descriptive names lead to two ways mon can differ: they can have different names, or they can have the same name but be drawn differently acheter viagra allemagne. Different members of a family might use minor variations on the family mon, and different families that happened to use the same mon (say, in different provinces) ended up having slight differences due to artistic chance. These minor differences might not be expressed in the simple language of mon names, and would not be great for recognition in the heat of battle, but were in some cases taken seriously as a means of distinction. When a variant became well-known enough, it got its own name of the form “Family Charge”; e.g., the “Aoyama Coins”2, to distinguish it from other identically-named mon. Here are several different bellflower mon: the plain bellflower, two slightly-different but identically-named bellflowers in a circle enclosure, and a ‘shadowed’ or outline bellflower.

This gives you a taste of what common samurai mon might look like. We’ll go into more of the history and possible elements for mon next time.

Mon: Japanese Crests

Mar 22nd (a Tomobiki (友引))

Mon, or Japanese crests, are one of my favorite Japanese design elements. Mon served much the same purpose as European heraldry: they were used for identification on the battlefield, to mark personal property, and to show family relationships, and sometimes they were given by a superior as a mark of honor. Mon are much simpler, design-wise, then European devices, however. For one thing, mon are monochromatic: color is not considered part of a mon, and the same mon could be drawn white on black, blue on yellow, or any number of other combinations. Secondly, while European devices can be divided in all sorts of different ways and incorporate a large variety of charges, mon tend to be of a few simple designs: one to eight or so copies of a single element, possibly in an enclosure of some sort. There are some patterns that incorporate two elements, but mon never reached anywhere near the density of European devices. Mon favor plant motifs, with the animal motifs favored in Europe quite rare, with the main exception being occasional birds.(JM:Heraldry)

Design elements that would later be mon date back to the Nara period (710–784). These designs were initially used on carriages and clothing, and first saw widespread use in battle in the Kamakura period (1185–1333).(SH:7,12) They were used by the court nobility and by samurai up until the Edo period (1603–1868), when their use, under strict regulations, spread to actors and merchants. Mon are still used today, their clean designs lending themselves to corporate logos such as that of Mitsubishi, which is actually named for the mon used as its logo (“three diamonds”).

There are many interesting categories of mon I could discuss, but let me start with the big, obvious one: Imperial mon. The 16-petaled chrysanthemum has long been the symbol of the Imperial family. Some historians think it actually originated as a stylized sun, referring to the Imperial line’s heritage as descendants of the sun goddess. This was one of the few mon that had usage restrictions on it even before the Edo period; the mon proper was restricted to the Emperor’s household, with the variant of a 14-petaled chrysanthemum seen from the rear for imperial princes, and other variations used by other members of the imperial family at various times. Those who one the favor of the Emperor would sometimes be given permission to use a mon incorporating the chrysanthemum, such a crest being a symbol of imperial favor but also loyalty to the Emperor. Similarly, during their rule of Japan the Ashikaga shōgunate was given use of the paulownia (kiri) mon by the Emperor, and in turn would grant the right to use mon based on it to loyal followers.(SH:6)

Still, most mon were much less strictly defined, and I’ll discuss more about mon and variation another time.

Sealed Away

Mar 8th (a Daian (大安))

A while back, I mentioned a toy I made for drawing Japanese seals. So, what’s the deal with Japanese seals, anyway? Seals, called Inshō (印章), were used for means of authentication throughout Japanese history, in similar ways to how they were used elsewhere. They were generally made of stone, with a flat, generally square face where the seal is carved and a handle end that can be carved decoratively. Instead of being used with wax, Japanese seals, like seals in other East Asian countries, were used as stamps with ink to sign documents, from official proclamations and contracts to works of art.(en.wp:Seal (east Asia))

Read the rest of this entry »

Pillow Talk

Feb 22nd (a Sembu (先負))

The word “pillow” (枕 or ‘makura’) seems to have been a popular metaphor in Japan. We have the concept of a pillow book, a ‘public journal’ prose form conceptually similar to a modern blog, the most famous of which is The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon. There’s also various pillow-related imagery in Japanese poetry, for example the idea of a ‘grass pillow’ as a temporary bed while traveling. Finally, there’s the pillow word (枕詞 or ‘makura-kotoba’), the topic of tonight’s discussion.

Pillow words are conceptually similar to the epithets used in classical Greek and Roman epic poetry. They were descriptors with a fixed form frequently applied to certain words. In a Roman poems, you wouldn’t just talk about the dawn; you’d often say something like “rosy-fingered dawn”. Similarly, in Japanese poetry, you might talk about the “red-shining sun” (あかねさす日/akanesasu hi).(CJAG:364)

These descriptors share some of the same purposes as classical epithets. Epithets were chosen to fit into the strict meters of epic poetry; similarly, pillow words are generally 5 syllables, to fit easily into Japanese forms, almost always made up of 5- and 7-syllable lines. In addition, they let you show off your familiarity with poetic traditions, remind your audience of the associations of a place1, and simplify the poetic process by providing solid ready-made material. Unlike classical epithets, pillow words are rarely applied to people or gods; they more frequently are used with elements of nature, places, or other poetic imagery.Movie Fifty Shades Darker (2017)

Pillow words first show up in the Man’yōshū, the oldest extant collection of Japanese poetry, dating to the Nara period. Most makura-kotoba that show up in later poetry are taken from Man’yōshū poems, since the set forms and strong tradition behind these descriptors was their main purpose. In fact, because these phrases are so old and were held constant as the language evolved, the exact intended meanings of many are unclear. This and the fact that their primary purpose was not a denotative meaning can present challenges when translating poems with makura-kotoba.(en.wp:Makurakotoba)

To close, here is an example from Hundred Poets, Hundred Poems. Read the rest of this entry »

Pivot Points

Feb 15th (a Tomobiki (友引))

Japanese poetry traditionally putting strict limits on the number of syllables used, various figures of speech were employed to stretch those syllables as far as possible. One of my favorite is the kakekotoba, or “pivot word”.1 It’s a kind of pun based on using a single word twice for two different meanings. The way to think about it is this: come up with a sentence where a word would be followed immediately by a homophone. One of the two words can actually be longer, as long as the part that’s adjacent to the other word sounds the same. Then, when writing the sentence, only write the shared sounds once. Instead of a sentence having multiple possible interpretations, a word has multiple interpretations within a single sentence.(CJAG:366)

This doesn’t work all that well in English, but let’s give it a try anyways. Let’s say I’m writing a tanka about vampires. I might want to say “The kindred dread dawn’s swift coming.” Making ‘dread’ a kakekotoba, I can just say “The kindread dawn’s swift coming.”, saving one crucial syllable, and more importantly impressing my peers with my poetic cleverness. A slightly better example is “The sisters pine incense fills the air.”2

Kakekotoba work better in Japanese than in English for several reasons. Firstly, Japanese has a lot of homophones. Having a more limited set of syllables to build words from increases your chance of collision a lot; part of the reason the Japanese writing system is so complicated is to tell homophones apart. Secondly, phonetic spelling: if two words sound the same, they’re (most of the time) written the same way in hiragana,3 so you don’t have spelling conflicts like I did with ‘kindread’. Finally, Japanese grammar rules are a little more flexible about word placement, so it’s easier to get the proper juxtaposition.

Here’s a Japanese example from the Kokinwakashū (dating to 914, in the Heian Period). It uses one of the classic examples: the word “matsu” can either be the verb “to wait” or a pine tree. Here, the tree interpretation is actually the first part of the name for a specific kind of insect.

Following Directions

Feb 8th (a Shakkō (赤口))

A few weeks ago, I talked about Rokuyō, the six-day calendar cycle of varying auspiciousness. Another key part of Japanese astrology, or Onmyōdō1, was concerned with auspicious and inauspicious directons.(en.wp:Onmyōdō) Which directions were auspicious or inauspicious for a given person, along with monoimi (personally inauspicious days), were determined by Onmyōji, professional diviners licensed by the court. They depended both on the calendar and on the time of day, in a similar way to the Rokuyō.

These divinations weren’t limited to cardinal directions; 24 directions were used, associated with animals in the Chinese zodiac, the 10 calendar signs (each in turn a combination of one of the 5 elements2 and yin or yang), and one of the eight trigrams of the I Ching.(ja.wp:干支) These associations were often mapped out with ornate compasses along the lines of the following.

Read the rest of this entry »

Seals

Jan 25th (a Butsumetsu (仏滅))

Unexpected adventure leads me to post about something I mostly did over a year ago. Inshō is a Japanese seal generator: it takes a string of Japanese characters and draws a seal for you as an SVG. It’s not entirely the same as a year ago, though; it now shows you with color when it’s using Unicode character equivalences that make a given glyph iffier, and it no longer requires external font support. Have fun with it; when I’m a bit calmer I’ll find time to write a post actually explaining Japanese seals (in addition to that auspicious direction post I promised).